Better Coaching Blog

Building Confident Athletes: 10 Ways Coaches Can Shape Lifelong Success

Confidence isn’t just a personality trait—it’s a skill. And like any skill, it can be built, nurtured, and strengthened over time. For coaches at the high school and middle school levels, instilling confidence in young athletes is one of the most powerful and lasting contributions they can make—not just to the game, but to the athlete’s life. Confidence affects how an athlete performs, how they recover from mistakes, how they respond to challenges, and how they view themselves off the field. It’s the quiet engine that fuels resilience, growth, leadership, and success—not just in sports, but in school, careers, and relationships. Why Confidence in Athletes Matters Research shows that confident athletes perform better, make decisions more quickly, and demonstrate greater resilience when faced with failure. In fact, a meta-analysis in The Sport Psychologist found that self-confidence was positively correlated with athletic performance across a wide range of sports and age groups. Confidence in youth athletes also directly influences long-term mental health. According to the American Psychological Association, young people who feel competent and secure are less likely to experience anxiety and depression, and more likely to engage in healthy risk-taking and leadership roles. And let’s not forget what employers want. According to the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE), attributes like leadership, communication skills, and confidence rank at the top of the list of qualities sought in job candidates. All of these are fostered through athletics— especially when coaches take the time to build them intentionally . 1. Set Process Goals Over Outcome Goals One of the most effective ways to build confidence is to shift focus from results to process. Instead of setting goals like “win the conference title,” teach athletes to focus on things within their control: how hard they work in practice, how well they communicate, how much they improve from week to week. These are measurable, visible, and can be reinforced daily. When athletes focus on process-oriented goals, they learn that their self-worth isn’t tied to the scoreboard. They begin to see improvement as success. And when they feel successful, confidence follows. ✅ Coach Tip: Have each athlete identify one personal goal each week related to effort, attitude, or execution. Review progress privately and celebrate growth often. 2. Create a Culture of Constructive Praise Confidence thrives in an environment where athletes feel seen, supported, and valued—not just for what they do, but for who they are. Carol Dweck’s groundbreaking work on growth mindset teaches us that praising effort over innate talent leads to more motivated, resilient learners. The same applies in athletics. When you say “You worked hard on that shot” instead of “You’re a natural shooter,” you reinforce the value of effort and teach kids that confidence comes from mastery, not luck or genetics. Be intentional with your praise: Specific: “Great job calling out that screen on defense—that’s leadership.” Timely: Address it in the moment to reinforce learning. Effort-based: Praise the hustle, not just the result. 3. Let Them Fail… Safely Confidence doesn’t mean avoiding mistakes—it means learning how to respond to them. Coaches often feel the urge to protect kids from failure, but the reality is that athletes gain true confidence by working through adversity. Missed shots, turnovers, fouls, and bad plays are part of the game—and they’re part of life. Helping kids process failure is one of the most valuable gifts a coach can offer. ✅ Coach Tip: Normalize failure. Say things like: “Mistakes mean you’re trying something challenging.” “What did you learn from that rep?” “Let’s go fix it together.” Failure becomes less intimidating when it’s framed as a stepping stone rather than a stop sign. 4. Build Identity Beyond the Jersey Many teens (and pre-teens) anchor their self-worth in their sport. This makes it easy for confidence to plummet after a bad game or injury. Coaches can help athletes develop confidence that transcends wins and losses by seeing them as whole people. Talk about leadership, academic success, character, and community involvement. Highlight the athlete who helps clean up after practice, who mentors a younger teammate, or who shows courage in difficult situations. These moments reinforce identity beyond stats and deepen the roots of true confidence. 5. Empower Athlete Voice Confidence grows when athletes feel heard. Invite athletes to be part of game plans. Ask them what they see on the court. Let captains lead stretches or discuss team values. When athletes feel like their voice matters, they show up differently. They stand taller, speak louder, and play more freely. You don’t have to give away control—you just have to open the door to collaboration. 6. Use Visualization and Mental Reps Confidence is linked to preparation. One proven strategy to enhance confidence is visualization. According to research published in the Journal of Sports Sciences , guided imagery and visualization can improve both performance and confidence in athletes, especially when used consistently in practice routines. Visualization strengthens the brain-body connection and gives athletes a mental blueprint to follow when the pressure’s on. ✅ Coach Tip: Take 3–5 minutes at the end of practice for team visualization. Walk them through game scenarios, success cues, and mental toughness strategies. 7. Eliminate the Fear of Embarrassment Confidence withers when athletes are afraid to make a mistake in front of their peers. To build a confident team, create a safe space where kids can experiment, mess up, and try again without sarcasm or ridicule—whether from teammates or coaches. Ban phrases like “C’mon, you should’ve made that,” and encourage your players to lift each other up. ✅ Coach Tip: Model the behavior. If you make a mistake while demonstrating, laugh it off. If a player says something vulnerable, thank them for their honesty. Show that courage, not perfection, is what earns respect. 8. Highlight the “Small Wins” Not every athlete is going to score 20 points or make the game-winning play. But every athlete has a moment that matters. Make it your mission to highlight the unnoticed wins—the box-out that led to a rebound, the smart rotation on defense, the hustle back after a turnover. When kids realize you’re watching the whole game, not just the scoreboard, they gain confidence that their effort counts. Create a “Hustle Highlight” or “Teammate of the Week” award. It goes a long way. 9. Encourage Reflection, Not Just Correction Instead of constantly correcting errors, ask athletes questions that help them reflect: “What did you see there?” “What would you do differently next time?” “Why do you think that worked?” This coaching approach builds confidence in their decision-making and helps them take ownership of their learning. 10. Be Their Mirror Finally, remember this: athletes often see themselves the way you see them. If you consistently believe in them—even when they don’t believe in themselves—you become a mirror they can trust. Your words, your tone, and your body language carry weight. If you treat them like they’re capable, resilient, and valuable, that belief will take root. The late Earl Nightingale famously said: “We become what we think about.” Help your athletes think about what they can become—not what they’re afraid of becoming. Final Thoughts Confidence isn’t just a nice bonus. It’s foundational. Confident athletes aren’t just better teammates—they’re better communicators, better leaders, and better prepared for life outside of sports. Whether you coach varsity or JV, Freshman, middle school, or in youth sports, you have the incredible power to plant the seeds of self-belief that will bloom far beyond the field or court. The strategies above don’t require extra time or resources—they just require intention. So, to every coach reading this: thank you. Your belief in a young athlete may be the belief that shapes their future.

The Calm Before the Kickoff: 5 Smart Moves for Fall Sports Parents to Make This Week

If you're a fall sports parent, this might be your last quiet week until the whirlwind begins. Practice schedules, game nights, last-minute runs to the store for forgotten cleats—it's all about to hit full speed. But this brief pause before the season starts is more than just a breather. It's a golden opportunity. Before whistles blow and team huddles form, use this moment to set your family—and your athlete—up for a great season. Whether your child is gearing up for middle school cross country or starting under Friday night lights, here are five smart moves you can make this week to start the season strong. 1. Get Clear on Expectations—Before the First Conflict As athletic directors and coaches, we spend a lot of energy communicating our program's expectations—but we know not everyone reads the handbook cover to cover. This is your chance as a parent to review the key expectations for your child’s team, whether it’s: Academic eligibility rules Communication guidelines (chain of command, 24-hour rule) Attendance policies Playing time philosophy Social media rules Take a few minutes this week to re-read the preseason packet or athletic code of conduct your school provided. If there hasn’t been a parent meeting yet, now’s the time to prepare thoughtful questions or even reach out for clarification. Knowing the rules upfront avoids tension later—and gives your athlete a strong foundation for understanding how to handle challenges with maturity and perspective. Pro Tip: If your athlete is a freshman, take time to explain what “team commitment” actually looks like in high school. It’s a step up from youth league or middle school expectations. 2. Prep the Calendar—and the Car You already know the calendar's about to explode with scrimmages, pasta dinners, team pictures, and more. But don’t wait until the first Monday of two-a-days to scramble. Use this quiet week to: Add all known game/practice dates to your calendar Block off family obligations, church nights, or special events Coordinate carpools with other parents (save your sanity early) Build a simple “athlete emergency kit” for the car That last one might sound small, but it’s huge: keep a clear bin in your trunk stocked with deodorant, extra socks, a water bottle, a towel, snack bars, and an old pair of cleats. Your future self will thank you—probably while sitting in traffic on the way to a field 30 minutes from home. Bonus Tip: For multi-sport households, color-code your calendar. It helps reduce double-booking and forgotten obligations—especially if you’re juggling band concerts, cheerleading, or soccer, too. 3. Talk to Your Athlete—Before the Season Talks to Them You’ll hear a lot of instructions coming from coaches once the season starts. But before that happens, it’s worth checking in quietly with your athlete: What are they hoping to achieve this season? Are they excited—or secretly nervous? Do they understand what being a great teammate looks like? This doesn’t need to be a formal sit-down. It can happen over dinner, during a car ride, or while walking the dog. But this conversation could be one of the most important moments you have all season. It sets the tone. You may find out your child is anxious about a new coach. Or that they’re more focused on earning a varsity letter than you realized. Or that they’re quietly considering quitting—before the season even begins. Don’t assume you know. Ask. And then, listen. 4. Do a Social Media Check-Up (Seriously, Do It) Whether your child is in 7th grade or heading into their senior year, this is a perfect time to do a quick audit of their online presence. Why? Because college coaches and recruiters are watching. Even if your athlete isn't thinking about college sports, their teammates might be—and one bad tag or inappropriate post can reflect poorly on the whole program. And what is put on social media now, a future employer can easily find. According to a 2020 survey from Cornerstone Reputation , 90% of college coaches said they review the social media of potential recruits. And that number has likely only grown. What should parents and athletes look for? Delete or untag any inappropriate content (even if it’s “just a joke”) Review bios and profile pictures for maturity Set privacy settings wisely Follow or engage with positive athletic accounts or role models This is also a chance to use social media well: post highlight videos, workout clips, or team bonding moments that reflect leadership, commitment, and growth. For a deeper dive, check out our podcast episode, “Social Media and Recruiting: What Athletes and Parents Need to Know.” It’s a must-listen before the fall season. Talkin' with the AD podcast - subscribe here! Talkin' with the A.D. podcast 5. Choose Your Sideline Behavior—Now, Not Later Let’s be honest—none of us plan to become “that parent.” But the mix of adrenaline, high expectations, perceived bad officiating, and social pressure can turn even the calmest parent into a sideline tornado. So, before the first game whistle blows, ask yourself: What kind of sports parent do I want to be this season? Maybe it’s: The cheerleader who stays positive—even in a loss The encourager who focuses on effort and attitude, not stats The quiet supporter who lets the coach do the coaching Make a personal commitment now, not midseason when emotions are running high. And remember: “Your athlete is watching you more than you’re watching them.” The way you handle calls, playing time, or rival teams teaches them more about character than any pep talk ever could. Final Thought: A Calm Start Leads to a Better Season Fall sports are about more than wins and losses. They’re about growth, resilience, and relationships. Starting the season with clarity, preparation, and calm will give your child—and your whole family—the best shot at a meaningful, healthy, and memorable experience. So take advantage of this quiet week. Set the tone now. Because once kickoff comes, it’s game on. Want more parent-focused sports tips? Subscribe to the Talkin’ with the A.D. podcast or check out BetterYouthCoaching.com for weekly content that helps you support your athlete the right way. And remember: stay positive, stay hungry, and go get better every day.

How to Have the “Playing-Time” Conversation Without Torching Bridges

Few topics in high-school and youth sports generate more anxiety than playing time . Parents naturally want their child on the field; coaches must balance individual development with team success; athletic directors juggle both sides while guarding a positive culture. Handled poorly, a single talk about minutes or positions can scorch trust and ripple through an entire program. Handled well, it can strengthen relationships, clarify expectations, and model the very sportsmanship we want kids to learn. Below is a playbook—roughly the length of a good inning-change—that keeps bridges intact and everyone moving forward on the same team. 1. See the Situation Through Two Sets of Lenses Parents: the “Love Blinders” Parents come to the table as the lifetime president of their child’s fan club. They’ve cheered through rain-outs, car-pooled to 6 a.m. workouts, patched scraped knees, and bought the 2-sizes-too-big cleats because “growth spurts happen.” It’s impossible—and frankly undesirable—for them to be objective. That partiality is love, not malice. A basketball team huddles together, sharing a moment of unity and motivation before their game in the gym. Coaches: the 30-Thousand-Foot View Coaches, meanwhile, watch every drill, chart effort, and consider chemistry, strategy, and safety for an entire roster. The camera angle is wider. What feels like an eternity on the bench to one family may represent the best puzzle piece for the whole squad. Key Mindset: A productive conversation starts when each side acknowledges the other’s vantage point is real and valid, even if it isn’t complete. 2. Set the Stage Before Emotions Boil Publish playing-time philosophies early. Add them to preseason packets, parent meetings, and team handbooks. Clear criteria—practice effort, tactical fit, attitude, academic standing—reduce mystery. Create designated office hours. Coaches who offer specific windows for questions (“Tuesdays, 4-5 p.m.; no game days”) signal openness and prevent a sideline ambush. Model curiosity with kids first. Encourage athletes to ask, “Coach, what can I do to earn more reps?” When players own the dialogue, they gain agency and parents gain context. 3. Prepare Like It’s Game Day For Parents Clarify Your Goal. Is it information, a developmental plan, or venting frustration? Aim for growth. Gather Evidence, Not Rumors. Note concrete moments you observed: “I noticed Jamie took only one defensive rotation the last two matches.” Avoid comparisons (“Sam plays because his dad is on the booster club”). Practice Neutral Language. Replace “You’re not giving my daughter a fair chance” with “I’m hoping to understand how you evaluate outside hitters.” For Coaches Review Your Metrics. Bring practice logs, hustle scores, attendance sheets, and video clips. Facts defuse feelings. Anticipate Questions. Know how each athlete ranks in the skills that dictate time: defensive reads, shot selection, communication, etc. Ready an Improvement Map. Walk away from the meeting with a concrete next step (“If Carter can complete the conditioning ladder in 55 seconds consistently, we can add him to the varsity rotation”). Two soccer players compete fiercely for control of the ball on a sunny day, showcasing their skills and determination on the grassy field. 4. Conduct the Conversation:

Before any minutes or metrics are discussed, the coach or AD should take sixty seconds to lay out the ground rules that keep the meeting constructive: no blaming, no yelling, no accusing or name-calling, and absolutely no talking about athletes who aren’t in the room (or related to the parent in the room). Everyone agrees to speak one at a time, refrain from interruptions, allowing each other to speak and respond to questions or statements, and keep voices at a respectful level. Setting these expectations up front creates a safe space where concerns can be aired, solutions explored, and every participant—parent, coach, and student-athlete—feels heard and respected. Six Best Practices Step Why It Works Nuts & Bolts 1. Start With Shared Purpose Aligns both sides around the child’s growth & team success “We both want Emma to improve and the team to thrive.” 2. Ask Before Telling Lowers defenses, surfaces misconceptions “What have you noticed about Liam’s role lately?” 3. Listen Actively Validates emotions even when you disagree Eye contact, paraphrasing: “So you’re concerned his minutes dipped last week.” 4. Present Objective Data Shifts focus from opinions to observable facts Show practice grades or game analytics. 5. Offer a Development Path Turns frustration into motivation “If he refines first-touch accuracy to 80 %, that could open rotation opportunities.” 6. Close With Next Steps & Check-In Prevents limbo, reinforces partnership “Let’s revisit in two weeks after we track these drills.” 5. Avoid the Triple Tech Fouls Email Novel-Length Complaints. Written tone is easy to misread; schedule a face-to-face or call instead. Bleacher Whisper Campaigns. Venting to other parents rarely reaches the coach—and often reaches the athlete. “My Kid or I Quit” Ultimatums. They box everyone in and rarely yield the desired result. Leave exits off the table until every option to grow has been tried. A focused athlete prepares for her pole vault attempt, showcasing determination and concentration amidst the outdoor event. 6. Athletic Directors: The Bridge Builders ADs can be proactive referees: Train Coaches in Communication. Workshops on conflict resolution pay off in fewer escalated complaints. Provide a Clear Chain of Command. Parents should know to approach the coach first, then the AD if truly unresolved, and finally administration. Celebrate Transparent Programs. Highlight teams that publicly post playing-time criteria or run mid-season parent check-ins; spotlight what right looks like. 7. When the Answer Is Still “Not Yet” Sometimes, despite collaboration, an athlete’s role remains limited. Here’s how to keep hope alive: Redefine Success Metrics. Playing time isn’t the only scoreboard. Improved practice habits, leadership, or mastering a new position are wins. Explore Alternative Roles. Stats crew, mentorship of younger players, or a specialty skill (e.g., pinch-runner) keep athletes engaged. Plan for the Future. Younger athletes, especially, need the reminder that bodies and rosters change; patience today can pay off next season. 8. Closing the Loop A single respectful conversation rarely fixes everything, but it plants seeds of trust . Parents feel heard; coaches feel supported; athletes see adults modeling composure under pressure. When the next tough issue arises—injuries, position changes, college recruiting—there’s relational capital in the bank. Final Whistle In youth and high-school sports, playing time is more than minutes on a scoreboard; it’s a proxy for identity, effort, and dreams. Approach the conversation with empathy, data, and a shared commitment to growth, and you won’t just preserve bridges—you’ll build stronger ones. And that, ultimately, helps every athlete walk off the field better prepared for the bigger games life will throw their way. Stay positive, keep learning, and remember: we’re all on the same team.

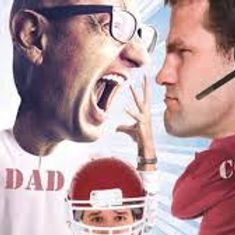

Blinded by Love: The Truth About Playing Time and Parental Bias in Sports

We’ve all heard it—or maybe we’ve even said it: "My kid should be playing more." "He works so hard. He just needs a chance to show what he can do!" "She’s just as good as that starter." These thoughts are completely natural. In fact, they’re rooted in something beautiful: love. But that same love can sometimes cloud our judgment, especially when it comes to youth and high school sports. In the world of youth and high school sports, there’s no stronger force than a parent’s love. It’s what drives early morning practices, endless carpools, and late-night pep talks. But that same love can unintentionally cloud how we view our child’s role on the team—especially when it comes to playing time. This natural and common phenomenon is what I refer to as “love blinders.” That’s not a judgment—it’s an explanation. And it can help all of us, especially sports parents, better understand the emotional lens through which we see our kids and their athletic experiences. What Are Love Blinders? “Love blinders” are the subconscious filters parents develop from watching their children grow, work, and compete. They form through years of investment—emotional and otherwise. You’ve seen your child overcome struggles, put in hours of work, and battle through disappointment. So when they don’t get the playing time you believe they deserve, it doesn’t just feel unfair—it feels personal. That feeling is valid. But it may not always align with the reality coaches see day to day. Why the Disconnect Happens What coaches and parents see can be very different. Here's a simple truth: your love sees effort, not always execution and you see much more of the positive and perceived potential—and that’s okay. Love focuses on the journey. Coaches have to focus on the game plan. Coaches watch athletes through a different lens: Performance in practice (consistency, focus, execution) Team chemistry (attitude, communication, leadership) Game readiness (tactical fit, decision-making under pressure, proper positioning based on scheme, etc) Effort in unnoticed moments (conditioning, warm-ups, non-glory roles) And while parents often only see the games, coaches see everything else. It’s their job. The graphic below offers a side-by-side look at what matters most to each group when it comes to playing time: The Emotional Weight of Watching From the Sidelines When your child doesn’t play as much as you hoped, it’s natural to feel a little helpless, maybe even defensive. You want to shield them from pain. That’s what parents do. But here’s a deeper truth: adversity can be a gift in amateur sports. Sitting on the bench, facing competition, learning to ask, “What can I do better?”—these are powerful moments of growth. The best athletes—and the best adults—learn how to respond to challenges, not avoid them. As parents, we can’t, and shouldn't remove all obstacles. But we can walk beside our children as they navigate them. How to Take Off the Love Blinders (Even Just a Little) You don’t have to be completely unbiased. In fact, it’s probably not possible. But there are a few things you can do to gain perspective and help your child thrive: 1. Be Curious, Not Combative Instead of jumping to conclusions or complaints, ask questions. Encourage your child to talk directly with the coach: “What can I improve to earn more time on the field?” That kind of question builds trust and accountability. And coaches should be able to answer that question. 2. Separate Effort From Entitlement Just because your child works hard doesn’t mean they’re entitled to minutes. Effort doesn't always equal outcome. In a competitive setting, everyone is working hard. Playing time comes from execution, not just effort. 3. Use Video to Gain Objectivity Try filming a game and watching it back later. You may see things you didn’t notice the first time. It’s one of the best ways to view your child’s performance through a coach’s eyes. 4. Focus on Growth, Not Glory Ask yourself: What do I want my child to gain from sports? Confidence? Resilience? Teamwork? Leadership? Those things can be built just as much—if not more—during hard seasons than during high-stat ones. 5. Watch the Whole Team, Not Just Your Kid When you shift your focus from “my kid” to “the team,” you’ll better understand the coach’s decisions—and you’ll likely gain more respect for the full effort behind each game plan. A Note to Coaches Coaches, parents don’t speak up because they want to make your job harder. They speak up because they love their kids. If you lead with empathy and communicate clearly—even when delivering hard truths—you’ll turn tension into trust more often than not. Playing time will always be a sensitive issue, but how we respond to it—as parents and coaches—can set a powerful example. Love Without Losing Sight Being a sports parent is tough. You care deeply, you see the effort behind the scenes, and you just want your child to feel seen and rewarded. That doesn’t make you difficult—it makes you loving. But love alone doesn’t always tell the whole story. The key is balance. Cheer for your child. Advocate when necessary. But also trust the process, support the coach, and teach your child how to respond with grace, grit, and growth. In the end, the lessons your child carries with them won’t just come from playing time. They’ll come from what they learned through it all—on the bench, in the game, in the locker room, and at home.

The Role of Parents in Youth Sports: Encouragement vs. Pressure

Youth sports are supposed to be joyful laboratories where children tinker with movement, teamwork, and perseverance. Yet a National Alliance for Youth Sports poll suggests that about 70 percent of kids abandon organized sports by age 13, citing a loss of fun as the main reason . CoachingBest Digging beneath that sobering statistic, researchers repeatedly identify one root cause: when parental enthusiasm morphs into pressure, the game feels less like play and more like work. PubMed PMC Healthy competitive pressure can absolutely play a constructive role—but only once athletes have the cognitive and emotional tools to interpret it productively, a developmental threshold most teens reach later in their high-school years. By that stage, their brains have advanced enough in abstract thinking and self-regulation to grasp that stress is information, not danger, and to deploy coping skills such as goal-setting, reframing, and controlled breathing. Moderate, well-scaffolded demands then become “eustress,” stimulating the inverted-U sweet spot described by the Yerkes-Dodson Law , where arousal sharpens focus and commitment without tipping into anxiety. Research shows that older adolescents who are exposed to this calibrated strain—through tougher practices, higher stakes, and honest performance feedback—develop greater mental toughness and self-efficacy, traits that buffer them against burnout and even enhance academic resilience. Crucially, though, that same load applied too early, before psychosocial maturation catches up, merely overwhelms younger athletes. Think of pressure as a weight room for the mind: the load should increase only when the athlete’s “muscles” are strong enough to lift it. Why parents set the emotional tone Let's talk about parents role in youth sports. From car-ride conversations to sideline body language, parents act as an “emotional thermostat,” subtly cueing children on what matters most. Studies show that the climate parents create—supportive or controlling—shapes not only day-to-day enjoyment but also long-term commitment to sport. Adolescents who perceive consistent, caring involvement report higher fun, usefulness, and importance in their activities, while those who sense evaluative pressure are far likelier to drop out. PubMed Psychologists explain this through Self-Determination Theory , which says people thrive when three needs are met: autonomy (choosing), competence (feeling capable), and relatedness (feeling connected). Balance is Better Encouraging parents feed those needs; pressuring parents thwart them, often unintentionally. Baylor College of Medicine clinicians note that constant appraisal and comparison elevate cortisol and trigger performance anxiety, undermining both health and performance. Baylor College of Medicine The fine line in action Below is the same quick-reference chart you liked—an at-a-glance reminder of how similar words and gestures can land very differently. Encouragement Pressure “Have fun—play your game.” “We drove two hours for this/We paid $250 for this; don’t waste it.” Process praise: “Great hustle on defense.” Outcome praise only: “Did you score?” Post-game chat when the child is ready Instant critiques in the car Respecting the coach’s voice Shouting instructions over the coach When the line is crossed Children exposed to chronic pressure report higher anxiety, lower intrinsic motivation, and a stronger tendency to define self-worth by stats or wins. Self Determination Theory Creativity shrinks, mistakes feel catastrophic, and the very skills parents hope to nurture—resilience, decision-making, joy—stagnate. In families, tension often spills beyond the field: ice-cold rides home, reluctant conversations, even avoidance of practice altogether. A conversational self-check One simple barometer is the “first question test.” After practice or a game, do you lead with “Did you win?” or “How did you feel out there?” The former orients the child to outcome; the latter invites reflection on process and emotion. Think, too, about whether you can list hobbies your child loves that have nothing to do with sports. If not, your identity as a family may be narrowing more than you realize. Turning encouragement into daily habit Rather than memorizing dos and don’ts, weave support into normal routines: Say the magic phrase: A calm “I love watching you play” places unconditional pride above performance. Share goal-setting: Sit down pre-season and let your child name two process goals—say, improving left-foot passing or learning a new swim stroke—alongside any outcome aspirations. Keep the ride light: On the way home, leave analysis until emotions settle. Talk music, friends, or grab a milkshake instead. Model composure: Your measured reaction to a blown call or rough loss is a live master-class in emotional regulation. Champion multi-sport seasons: Data link varied movement patterns with lower injury rates and higher long-term motivation. PMC Celebrate character moments: A sincere apology after a foul or helping an opponent up deserves the loudest cheer in your repertoire. Partnering with coaches and clubs Positive cultures grow fastest when coaches invite parents in as collaborators. Pre-season orientation meetings that outline communication channels, sideline etiquette, and shared definitions of success reduce confusion later. Distributing “cheer cards” with sample supportive phrases or sharing mid-season “process stats” (e.g., deflections, completed passes, personal best effort scores) widens the lens beyond the scoreboard and keeps everyone rowing in the same motivational direction. If you realize you’ve slipped into pressure Awareness is step one. A straightforward apology—“I pushed too hard today; I’m sorry”—can reset the tone immediately. Re-focus on effort, solicit your child’s perspective, and, if patterns persist, consider parent-education workshops or a brief consultation with a sport-savvy counselor. Research shows that targeted parent programs can reduce controlling behaviors and improve athlete motivation within a single season. Self Determination Theory Keeping the joy in the journey Your child’s sports story is theirs to write. By choosing steady encouragement over performance pressure, you protect the fun that drew them to the game, nourish their psychological needs, and cement a relationship that will outlast any trophy shelf. Years from now, the scoreboard will be forgotten, but the feeling of hearing “I love watching you play” never will.

10 Ways I've Found the Perfect Balance Between Competition and Fun in Youth Sports

Youth sports are not just about competition; they are crucial for children's growth, learning, and friendship-building. As a sports parent, I understand how challenging it can be to find that balance between having fun and being competitive. A focus too heavily on winning can take away the joy of playing, while an overly relaxed attitude might diminish kids’ motivation to improve. In this post, I'll share ten effective strategies that have helped me create an environment where my kids can thrive both on and off the field. 1. Focus on Skill Development To nurture a love for sports, prioritize skill development over winning. Encourage children to practice fundamental skills like dribbling, throwing a baseball or softball, or shooting for a goal in soccer. For example, rather than fixating on game scores, celebrate improvements, such as moving from five successful passes to ten in a week. This shift in focus allows them to appreciate their growth and enjoy playing more. 2. Set Realistic Goals Setting achievable goals is key for young athletes. Work with your children to create objectives they can realistically reach. For instance, a ten-year-old could aim to improve their sprint time by one second over the season or master a specific dribbling drill. Meeting these goals provides a sense of accomplishment and keeps their experience rewarding. 3. Celebrate Small Victories Recognizing small successes is crucial for motivation. Celebrate achievements, no matter how minor they seem. Did your child make a great pass in practice? Acknowledge it! Did they stay focused through an entire game? That’s worth celebrating too. Recognizing these moments can create an encouraging environment that inspires kids to keep pushing themselves. 4. Encourage Teamwork Promoting teamwork within youth sports enhances enjoyment. Kids work better when they feel part of a supportive team. Encourage them to communicate, help each other out, and build friendships. Research shows that children who engage in teamwork report a 20% higher satisfaction rate in their sports experience. This camaraderie not only boosts enjoyment but fosters personal growth as well. 5. Promote a Positive Attitude Your outlook as a parent profoundly impacts your child's experience. Show enthusiasm and maintain positivity, even in challenging times. Remind them that the main goal is to enjoy the game. A study conducted by the American Psychological Association found that children whose parents displayed a positive attitude were 25% more likely to develop a lasting love for sports. 6. Create Fun Practices Practices should go beyond drills and competition. Infusing fun games into training can keep the mood light. For example, instead of traditional sprints, opt for relay races that encourage skill while sparking joy. Kids are more likely to look forward to practice when they know it’s going to be fun. 7. Be Mindful of Over-Competition Recognize when the competitive spirit becomes overwhelming. Keep an eye on your child's stress levels and emotional responses. If you notice signs of burnout or anxiety, reset expectations. Ensuring your child has downtime can lead to better long-term performance and enjoyment. A balanced approach is essential for their mental health and overall sports experience. 8. Encourage Sportsmanship Instilling a sense of sportsmanship can greatly enhance the enjoyment of competition. Praise your child for showing respect to opponents and congratulating them for a good game, irrespective of the outcome. This promotes the value of fair play and reminds them that participating is more important than winning. 9. Mix Up Sports and Activities Encourage kids to participate in various sports and activities to keep their experience refreshing. For example, rotating between soccer in the fall and basketball in the winter can prevent burnout. A 2022 survey found that children who engaged in multiple sports scored 30% higher in overall athletic skills compared to those specializing too early. 10. Involve Yourself Getting involved in your child's sports journey can enhance their experience. Attend games, cheer them on, and engage with other parents. Your active participation shows support and enthusiasm, making the experience more enjoyable for them. Plus, it opens doors to building friendships with other parents who share similar interests. Finding the Right Balance Finding the perfect balance between competition and fun in youth sports is vital for a child's positive experience. By concentrating on skill development, acknowledging accomplishments, and fostering a positive atmosphere, we can create a space where kids enjoy themselves and thrive. Remember, youth sports should be about fun and personal growth rather than just winning. Implementing these strategies has helped my children enjoy their sports journey and gain valuable skills they will carry into adulthood. Together, let’s make youth sports a joyful adventure!

10 Key Insights on Balancing Specialization and Diversity in Youth Sports

Published by Morgan Sullivan, Athletic Director, Coach Youth sports have evolved dramatically over the years, with parents and coaches often faced with the challenge of how best to guide athletes in their developmental journeys. The debate surrounding specialization versus diversity in youth sports has gained significant traction, emphasizing the need for a balanced approach. This post aims to provide 10 key insights that will help sports parents and coaches navigate the delicate balance between specialization and diversity in youth sports. 1. Understanding Sport Specialization and Diversity Specialization in youth sports refers to the focused engagement in a single sport during a significant part of the year. It is often influenced by the perception that early specialization leads to greater success. In contrast, diversity means encouraging young athletes to participate in multiple sports, which can contribute to varied skill development and a more enjoyable athletic experience. Both paths have their advantages and disadvantages, and understanding them is crucial for making informed decisions. 2. The Importance of Skill Development Encouraging skill development through diverse sports participation helps in fostering well-rounded athletes. Young athletes exposed to different physical demands will learn various techniques and strategies that enhance their overall athletic performance. When children try different sports, they not only develop a broader range of physical skills but also learn essential life skills such as teamwork, communication, and problem-solving. These abilities transfer across sports and can give them a competitive edge when they choose to specialize later on. 3. Physical and Mental Health Benefits Participating in multiple sports has proven benefits for physical health, including reduced injury risk due to overuse and improved cardiovascular fitness. Engaging in various physical activities maintains enthusiasm and motivation, encouraging a lifelong love for sports. Mentally, a diversified approach allows for reduced pressure and stress, which is often associated with specialization. When young athletes dabble in various sports, they can experience joy and satisfaction without the emotional toll that comes with the high expectations of a single sport. 4. The Role of Coaches and Parents Coaches and parents play a vital role in shaping young athletes' experiences. They should be aware of the potential pitfalls of early specialization, such as burnout and injury, and advocate for a balanced approach. Encouraging young athletes to explore a variety of sports fosters an environment where they can discover their passions freely. Coaches should provide opportunities for multi-sport participation and emphasize the importance of skill development over performance metrics alone. To be perfectly clear, hearing a parent provide the reason, "My kid only wants to play _____ sport" is a poor reason to allow early specialization. Youth athletes lack the understanding expected of parents. This is where the parent needs to step in and make the decision for the athlete. 5. Recognizing the Signs of Burnout Burnout is a serious issue affecting young athletes, often stemming from relentless pressure to perform in a specialized sport. It's important for parents and coaches to be vigilant in recognizing the signs, such as a decline in enthusiasm, fatigue, or dissatisfaction with sports. When young athletes exhibit these signs, it may be time to re-evaluate their engagement and consider promoting a more diverse range of activities. Encouraging a break or a shift to another sport may reignite their passion and energy. 6. Building Social Connections Participation in various sports allows young athletes to build a broader social network. Engaging with different teammates, coaches, and peers fosters friendships and encourages collaboration and camaraderie. While specializing can lead to deeper bonds within a single sport, diversifying can introduce a wider community, which can be rewarding and enriching. These relationships can positively impact mental health and provide a support system that young athletes can rely on throughout their sports journey. 7. Lifelong Skills and Values Youth sports are not solely about winning or losing; they serve as a foundation for building lifelong skills. By participating in diverse sports, young athletes learn resilience, time management, and adaptability. These experiences are invaluable and can be applied far beyond the field or court. Moreover, children develop an understanding of sportsmanship, respect, and discipline, which are essential values not only in sports but in everyday life. 8. The Timing of Specialization Research suggests that the optimal time to specialize in a sport is in the high school years, allowing for adequate physical and mental maturity. During the early years, multidisciplinary experiences can arm athletes with the necessary skills and instincts that can be beneficial when they make the decision to specialize. By delaying specialization, young athletes can develop their love for the game rather than seeing it as a chore. This approach can greatly enhance their enjoyment and commitment to the sport. 9. Local Programs and Resources For families seeking a balanced approach, many local sports programs offer multi-sport opportunities designed for young athletes. These programs not only provide training but also prioritize fun, engagement, and skill development. It is essential for parents and coaches to research and take advantage of these resources, ensuring that young athletes enjoy a variety of experiences. Engaging in community programs can also enhance social connections, further benefiting young athletes. 10. Making the Decision Together Ultimately, the decision to specialize or diversify should be made collaboratively between the young athlete, their parents, and coaches. Open communication ensures that the athlete’s interests, goals, and mental health are prioritized in the discussion. Encouraging young athletes to voice their preferences will foster a sense of ownership over their sports journey. This empowerment can increase motivation and satisfaction, leading to more positive experiences in youth sports. Conclusion Balancing specialization and diversity in youth sports is essential for promoting healthy athletic development. By understanding the importance of skill acquisition, mental well-being, and social relationships, sports parents and coaches can better guide young athletes on their journey. Incorporating diverse experiences can equip athletes with the foundational skills and resilience needed for future specialization if they so choose. Ultimately, the goal should be to cultivate a love for sports that lasts a lifetime, setting the stage for success both on and off the field. In recognizing the unique needs of each athlete, adults involved in youth sports create a healthier, happier environment that nurtures the next generation of athletes. Let’s unite in embracing the balance between specialization and diversity, ensuring that every young athlete can thrive.

Sideline Etiquette 101

A Code of Conduct You’ll Actually Follow By Morgan Sullivan, Athletic Director & Coach Why We Need a Sideline Code On most weekends, the soundtrack of youth sports is a mash-up of whistles, cheering, and—too often—adults losing their cool. Nationwide, officials are walking away, participation in organized sports has slipped 13 percent since 2019, and many kids cite “pressure from parents” as a reason for quitting altogether. Project Play The irony? Every parent, coach, and athlete on the field wants the same thing: a positive, developmental experience. The disconnect comes when impulse overrides intention; when emotion trumps logic. That’s why the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) made “modeling sportsmanship” a 2024 Point of Emphasis, reminding schools to set clear expectations for everyone on game day. NFHS Below is a practical, bite-size code you can put on your refrigerator, in your team handbook, or on the back of season passes. No legalese—just habits that keep the focus where it belongs: on kids enjoying the game(s) they love. The 6-Point Sideline Code # Guiding Habit Real-Life Behaviors You’ll Actually See (and Hear) 1 Cheer Hustle, Attitude, Effort, Not Outcome “Great hustle, #7!” when an athlete dives for a ball. Applause for a textbook pick-and-roll, great rebound, when a player runs hard on a ground ball (even if they get thrown out). Parents high-fiving after a long rally, regardless of who wins the point. 2 Let Coaches Coach No verbs. Telling players what to do during the game is the role of the coach, not the fans in the stands. Yelling instructions to your athlete leaves the players confused at best, and often frustrated. Kids understand the roles - they want parents to support them, and coaches to instruct them. The loudest thing you yell is, “Let’s go, Tigers!” —never directions like “Pass left!” 3 Respect Officials — Always Questionable call? You exhale, maybe raise eyebrows, but words never leave your lips. We expect players to move on to the next play, fans should, also. After the game, you greet the ref with “Thank you for working today.” If another spectator starts chirping, you pivot conversation or offer a calm “Let’s keep it positive.” 4 Model Composure After a turnover you clap twice and sit back down—not stand up waving arms. Phone in hand? You’re recording highlights, not replay-sniping calls. Your facial expression resets as fast as the athletes move to the next play. 5 Celebrate Teammates Publicly, Critique Privately You shout out “Nice block, Lydia!” instead of “Come on, shoot faster!” When your child looks your way, you give a thumbs-up and a smile, not tactical signals. Any constructive feedback is handled by the coach. If your kid asks for your opinion, it's a welcomed conversation. Until then, it's not helping. 6 Leave the Venue Better Than You Found It Final horn sounds? You scan the bleacher for water bottles and programs. Help pick up trash from your area. High-five a volunteer ticket-taker on the way out. You exit chatting about the team’s grit, how much fun it was to watch the kids, and the good parts of the game, not the negatives about the officiating crew or the coaches. Use the Snapshot Test. If someone snapped a photo of the crowd at any point, you'd be proud of your physical behavior (facial expression, body language, etc.). That's sideline etiquette in action. For Parents: Turning Good Intentions Into Good Habits The Next Day Rule – Wait a full day before emailing the coach about playing time or strategy. Emotional distance breeds constructive conversation. Car-Ride Check-In – Start with a question, not an analysis: “What was your favorite moment?” Let them steer the talk. Sideline Buddy System – If you’re a chronic yeller, ask a friend to tap your shoulder when your volume creeps up. Praise the Process – Compliment things the athlete can control (effort, attitude) rather than stats. Research shows process-praise builds resilience. SAGE Journals For Coaches: Setting the Tone Before Opening Day Publish the Code Early – Include it in preseason packets and parent meetings. Assign a “Culture Captain” – A trusted assistant or team parent can defuse small flare-ups before they escalate. Model It Yourself – Officials will forgive a missed clipboard if you’re calm when calls go south. Enforce Consistently – A gentle reminder first, a more stern reminder second, an escort out if necessary. Consistency signals you value every athlete’s psychological safety as much as physical safety. For Athletes: Owning Your Half of the Equation Use a “Next Play” Mentality – Bad call? Mistake? Acknowledge, flush, refocus. Respect Up the Ladder – Officials, opponents, coaches, teammates—in that order. Lead from the Bench – Energy is contagious; make yours constructive. Guard Your Online Sideline – Comments on IG or TikTok count as spectator behavior. If it’s trash online, it’s trash in real life. What to Do When Tempers Flare Name It, Claim It, Tame It Name the emotion (“I’m frustrated”), claim responsibility (“I’m choosing my reaction”), then tame it (breathwork, drink of water, short walk). Use Official Channels File concerns with athletic directors, league reps, or governing bodies—not in real-time from the bleachers. Reset as a Community An occasional “sportsmanship timeout” announced over the PA can halt collective momentum toward negativity. The Ripple Effect Positive sidelines do more than create pleasant Saturdays; they help retain officials, keep kids in sports longer, and improve mental-health outcomes. A 2023 study in Clinical Pediatrics linked lower rates of negative spectator behavior with higher athlete enjoyment and retention across four sports. SAGE Journals When we model respect, athletes mirror it on the field—and later in boardrooms, classrooms, and family rooms. Putting It Into Action Print and Post – Turn the 6-Point Code into a one-pager for your next parent meeting. Share Winning Examples – Use social media to highlight great fan behavior as often as great plays. Measure What Matters – Survey officials and visiting teams each season about your program’s sportsmanship. Improvement here is as worthy as a win-loss record. Final Whistle Sideline etiquette isn’t about silencing passion; it’s about channeling it. When adults own their role as partners in the athletic journey—cheering skill, respecting officials, modeling composure—we create a culture where young athletes can compete fiercely and grow freely. Print the code, practice it, and pass it on. The next generation is already watching. References National Federation of State High School Associations. “2024 Points of Emphasis: Sportsmanship.” NFHS Positive Coaching Alliance. “8 Sideline Behavior Tips for Parents on Game Day.” devzone.positivecoach.org Aspen Institute Project Play. State of Play 2024 —Participation Trends. Project Play LaRowe, S. et al. “Adult Negative Spectator Behavior at Youth Sporting Events.” Clinical Pediatrics , 2023.

The Impact of Overbearing Parenting on Young Athletes: How Pushing Too Hard Can Shape Their Social Lives

As parents, we all want what's best for our children, especially when it comes to their future. For parents with young athletes, it’s easy to get caught up in the excitement of their potential. Whether it’s pushing them to be the best on the field, insisting they practice harder, or setting high expectations, the intention is often good: to help them succeed. However, there’s a fine line between encouragement and pushing too hard. When we internalize the social structure of sports — the need to win, compete, and achieve — we may unintentionally impose this mindset on our kids. This can lead to negative consequences, affecting both their athletic performance and social lives. Let’s take a closer look at why that happens. The Social Structure of Sports: A High-Stakes Game The social structure of sports is inherently hierarchical, with success and failure forming the foundation of how athletes are valued. At the core, athletes are constantly measuring their worth based on performance, striving to rise up the social ranks. This pursuit of success isn't just about winning — it’s about gaining accolades and recognition, rewards that are often internalized into their self-worth. The more success they achieve, the greater their sense of value. Parents, wanting the best for their children, naturally push them to succeed, believing that high achievement will ensure their future success. However, what they often fail to realize is that this drive for success, paired with the internalization of competitive values, can lead to psychological maladaptations. The Dark Side of Overbearing Parenting Children raised in environments where winning is prioritized face several emotional and social challenges: 1. Neuroticism – Constant pressure to perform can lead to anxiety and self-doubt. Children who feel they must always be the best may develop a tendency to overthink and second-guess themselves in social situations. 2. Aggression – The competitive nature of sports can breed aggression when not kept in check. If a child is taught to be aggressive to win, this mentality can spill over into other aspects of life, making it difficult to form healthy relationships. 3. Egotism – When parents focus on success and winning, children can become overly focused on their achievements. This emphasis on recognition fosters an inflated sense of self-importance, leading to egotistical behavior in adulthood. 4. Difficulty Handling Failure – The reality of life — and sports — is that no one wins all the time. Children who view failure as catastrophic may struggle with setbacks and avoid situations where they might fail, limiting their growth in other areas. The Long-Term Effects: A Misguided Framework Each of these can significantly affect a child in their journey into adulthood. For example, in a professional setting, someone who struggles with neuroticism might constantly second-guess their decisions, which could slow down project completion and create frustration among colleagues. In relationships, a person with an aggressive & "win-at-all-costs" mentality might approach disagreements with a partner as a battle to be won, leading to constant conflict and difficulty compromising. Similarly, someone with an inflated ego might dismiss the contributions of others, making it hard to collaborate or build trust. Lastly, a person who fears failure might avoid taking on new responsibilities or challenges at work or in their personal life, limiting their growth and hindering progress. How to Support Your Child Without Overdoing It So, how can parents support their young athletes without overdoing it? Here are a few key principles to keep in mind: 1. Emphasize effort over outcome – Praise the effort your child puts into practice and development, rather than focusing on wins and losses. Show them that improvement and growth are more important than any score. 2. Encourage balance – While sports are important, remind your child that life is about more than just being an athlete. Encourage them to explore other interests and hobbies that help them develop well-rounded skills and relationships. 3. Teach emotional resilience – Failure is a part of life. Help your child learn from setbacks and use them as opportunities for growth, rather than punishing failure. 4. Focus on relationships – Remind your child that the value of sports is not just individual achievement but also teamwork and building connections with others. Healthy relationships, both in and outside of sports, should come first. Conclusion It’s easy for parents to get caught up in the competitive world of youth sports, but it’s crucial to remember that our children’s emotional and social well-being should always come before any game. Overbearing parenting, especially when tied to the competitive framework of sports, can have lasting effects on their social lives. By focusing on effort, resilience, and balance, we can help our children develop into well-rounded individuals who can handle the challenges of life — both on and off the field. Citations Ginsburg, K. R. (2007). The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bonds. Pediatrics, 119(1), 182-191. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2697 Larson, R. W. , & Richards, M. H. (1994). Divergent realities: The emotional lives of mothers, fathers, and adolescents. Psychological Science, 5(4), 179-184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467- 9280.1994.tb00352.x Baumeister, R. F. , & Vohs, K. D. (2007). Self-regulation and the executive function: The influence of self- control on decision making. In Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13-30). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012657510-2/50003-0 Coakley, J. (2011). Youth sports: What everyone needs to know. Oxford University Press. Kohn, A. (1992). No contest: The case against competition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Holt, N. L. , & Dunn, J. G. (2004). A grounded theory of the roles of social and psychological factors in athletes' experiences of competition. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 16(2), 186-203. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200490465191 Smoll, F. L. , & Smith, R. E. (2006). Children and youth in sport: A biopsychosocial perspective. Kendall/Hunt. Author Bio Joel Kouame, LCSW, MBA, CAMS-II, is a New York-based mental health specialist and the owner of JK Counseling. He specializes in anger management, trauma, depression, and anxiety, offering trauma-informed, evidence-based treatments such as EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing), IFS (Internal Family Systems), and the Gottman Method. Joel is dedicated to helping individuals build resilience and emotional well-being through personalized care. He provides a safe and compassionate space for healing, working with clients to address underlying issues and enhance emotional health. For more information, visit JK Counseling or follow on social media at LinkedIn , Instagram , and Facebook .

THE PITFALLS OF 'MORE, YOUNGER' MINDSET

Why Starting Kids Too Early and Pushing Them Too Hard Can Backfire in Youth Sports